When Qian 钱 Doesn’t Buy Happiness

As China’s economic development powers on, common wisdom says Chinese people should be enjoying the fruits of their labor. So why aren’t they happier?

by Robson Morgan

Date Published: 12/22/2008

Studies show that smiling faces are all over China, though no more than there used to be. Photo by Chris Suderman.

It’s the rare economist who isn’t impressed with China’s economic performance over the past decades. By nearly any measure -- gross domestic product, exports, foreign investment, industrialization, productivity, and household consumption are just a few -- China has done exceptionally well since economic reforms were initiated in 1978. One measure of success, however, is often overlooked. While most assume that prosperity brings increased happiness, this has not held true in China. Life satisfaction rates among the Chinese have shown no signs of improvement, despite booming economic growth.

“Surveys show that people almost invariably think more income would make them happier,” said Richard Easterlin, professor of economics at the University of Southern California. “If economic growth were to raise people’s life satisfaction, you would certainly expect to see some evidence of it in China.”

The surveys, however, show no indication of a happiness boom following the country’s economic rise. “Three different surveys are consistent in not giving any indication of better life satisfaction,” Easterlin said.

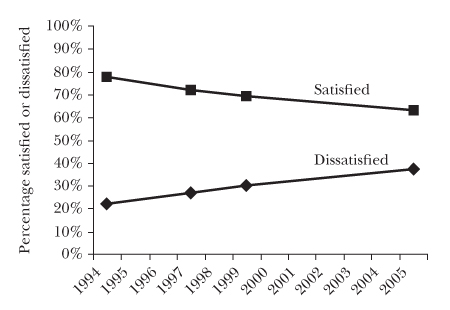

According to one such survey conducted by Gallup, Chinese household income grew 2 ½ times between 1994 and 2004, yet life satisfaction rates showed no improvement. While Chinese respondents expressed high levels of contentment with their current quality of life (63%), the number actually slipped from its 1997 high, when 72% expressed satisfaction.

The country’s economic boom over the past two decades has led to a considerable change in lifestyle for millions of Chinese. Access to modern living amenities yields a more comfortable life, yet while 82% of homes have color televisions and more than 450 million own mobile phones, Gallup found little to suggest a marked shift in public opinion on life fulfillment. The polling company also found that there is little data to support a difference in perceptions among urban dwellers and rural populations. In 2004, city residents polled at 64% while those in the countryside were only two points lower. Gallup interviewed more than 15,000 Chinese people from all parts of China to complete their polling.

Gallup Organization tracing the satisfaction of Chinese people over the years.

A 2007 Pew Global Attitudes survey provides a slightly different picture of China’s economic boom, noting that the country has seen an 11% gain in life satisfaction rates from 2002 to 2007. In contrast to the Gallup findings, developing countries like India and China expressed growing optimism for the future, polling 80% and 76% for those who believe their lives will improve in the next five years. The study, however, notes that 34% of those polled in China voiced their contentment while citizens in more developed countries like the United States and Canada claimed 65 and 71% respectively.

While China’s economic development has been profound, gains have been distributed unevenly throughout the country, possibly explaining the variance in public attitudes. Over 200 million people in China still live on less than US$1.25 a day.

Wang Fei, a graduate student at the University of Southern California, agrees with the findings. Wang was born in a small town in Hunan province, and later moved far away from her family to Beijing for college. She says that since the mid-1990s, although people’s lives have changed, people are not better off overall.

“People worry more about money in Beijing,” Wang said. “People’s incomes increase, but their spending also increases. In the city, there are more worries about money, jobs, and doing well in school.” Wang thinks she is happier when she is in her hometown, away from the busy, money-hungry city.

The economic progress China has made is impressive. Those statistics, though, do not convey how deeper pockets have also produced rising expectations.

“As people’s income goes up, [their] views of what they need to make them happy go up just as much,” said Easterlin. “An income increase in itself tends to increase people’s happiness, [but] since their comparison standard, the way they evaluate that income, is also rising at the same time, they end up no happier than before.”

Easterlin detailed this phenomenon in his influential 1974 paper “Does Economic Growth Improve the Human Lot?” Known by economists as the Easterlin Paradox, the concept centers around a key contradiction: while rich people in a society tend to be happier than their poor counterparts, wealthy countries show little or no indication of being happier than poor countries. The Paradox recently came back in to popular discussion after professors Justin Wolfers and Betsy Stevenson of the University of Pennsylvania voiced their criticism of the concept, noting modern polling practices that provide more accurate results.

The Gallup results, however, support Easterlin’s assessment and the difference in perceptions among urban and rural groups. According to the company, “While China's cities continue to grow rapidly because of massive internal migration, those Chinese who have remained in the countryside are now dramatically more likely than their urban counterparts to say they are satisfied with their own communities ‘as a place to live’.” The 2004 data highlights that while 52% of urban residents were satisfied, 65% of rural respondents voiced contentment with their local communities.

You need to upgrade your Flash Player

A second reason to explain why life satisfaction doesn’t necessarily increase with income, Easterlin explained during an interview, comes from certain destructive elements that occur along with economic growth. Although incomes rise and people are freed from poverty, there are costs. In China in particular, industrialization and modernization has required millions to migrate and live in burgeoning, overcrowded cities. Families are split up while workers scour the country for jobs, looking to grab a piece of the boom.

A July 2008 Pew Survey noted that while economic development has brought many benefits, ordinary Chinese increasingly worry about the social toll such rapid change can have. “Chinese people may be struggling with the consequences of economic growth. Notably, concerns about inflation and environmental degradation are widespread. And while most Chinese embrace the free market, there is considerable concern about rising economic inequality in China today.” The survey highlights the divide between China’s regions, noting that 23% of respondents from western China stated that paying for food was difficult while only 10% of those in the east felt similarly. 27% of those in western China also said unemployment was a problem compared to only 16% of those in the east. Environmental issues were a pressing concern for those living in central China -- 84% worried about air pollution in the region, the country’s top producer of coal.

Wang’s family had to live apart from each other.

“My father took a military job in Harbin [a large city in northeastern China far away from the Wangs’ hometown], but very quickly came back home. He wanted to stay with the entire family,” Wang said. Shortly after he returned, however, Wang left home to start graduate school at USC. “I think this [lifestyle] is very difficult.”

Samuel Ho, an associate professor in psychology at the University of Hong Kong, looks at the happiness issue from a different angle.

“In Chinese culture, some people do not want to feel too happy,” Ho said, explaining that in today’s Chinese society, little emphasis is put on personal happiness. “You work hard, and it is through suffering that you grow.” A 2006 study in the Journal of Clinical Nursing found that among Chinese people, perceptions of wellbeing are “significantly determined by a harmonious relationship with others in the social and cultural context.” Consideration of one’s own happiness often takes a back seat to the needs of the entire community. Overcrowded cities, hectic work schedules, and family separation may all contribute to a breakdown of this social relationship.

Ho explained that, for many Chinese, the actual trials of prosperity are often more important than the end result.

“Suffering itself has a different meaning than in the West,” Ho noted. “Suffering can lead to some positive outcome according to Chinese culture. So people would not like to let themselves be too happy.”

Ho emphasized that several consequences born from people’s fatter wallets may also undermine any future jumps in satisfaction.

“During the increase in economic development, people become more materialistic,” Ho explained, noting that materialism is often linked to increased susceptibility to depression. Ho cites another argument from American psychologist Barry Schwartz, which he explains as the “paradox of choice.” As money and more choices become available to consumers, people become increasingly less satisfied with their final purchasing decisions. Choosing takes more time and effort, and buyers find themselves less fulfilled knowing that could have had made a better decision. From finding the right job to purchasing the right consumer products, the rise of choice has complicated the life of Chinese people.

Ho, however, sees continued financial expansion having the potential to change Chinese views on happiness.

“If the culture in the future, like in the West, would allow people to focus more on their happiness and allow people to tell [others] they are happy…that would be better,” Ho said. Through increased attention to one’s own personal wellbeing and happiness, Ho believes that over time, economic prosperity will promote a culture of happiness in China.

Some people will benefit from the changes and reach a higher level of happiness than previously possible, Ho explained. Others, however, will suffer from these grand lifestyle shifts and find themselves depressed. Ho believes that overall, these two forces neutralize each other, balancing out any life satisfaction polls or indicators.

Looking towards the future, Easterlin believes that if modern Chinese society puts an emphasis on something besides simple rises in income, happiness levels could improve. An improved health care system coupled with greater social security and job protection programs may go far in improving public attitudes. Easterlin advises that the government could distribute extra money generated by economic development to address fundamental concerns of the people by improving these social support systems.

Ho also has a positive outlook towards China’s future.

“Increasing income is only one factor, but, if we can emphasize more on social support, emphasize more on spiritual life, and allow people to pay more attention to their happiness, that will certainly help.”

Robson Morgan is a graduate student in economics at the University of Southern California.

|

"While we appreciate the long hours and the effort that our Chinese counterparts have put into those trade discussions, quite frankly, in the grand scheme of a $300- to $500-billion trade deficit, the things that have been achieved thus far are pretty small. I mean, they're not small if you're a company, maybe, that has seen some relief. But in terms of really getting at some of the fundamental elements behind why this imbalance exists, there's still a lot more work to do."

- Rex Tillerson, US Secretary of State, at a press conference during Pres. Trump's visit to Beijing, Nov. 9, 2017

|