Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao and President Hu Jintao.

Wen Jiabao never survived a long march. He never founded a republic, never had a little red book filled with quotations, and never swam across the Yangzi. But perhaps it is his simplicity that attracts so many young Chinese to the Premier. He is responsible, caring, and uncomplicated. No frills, no surprises…Wen is, simply, a grandpa.

"We have always been touched by the people's Premier," said Shiqing, a frequent contributor to one of the many fan sites dedicated to Wen and President Hu Jintao. "We can see this from his cotton-padded jacket, which he has worn for more than a decade, and from his trips to the snow-struck regions, Wenchuan earthquake and so on."

Immediately following the May 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, the Premier flew to the disaster zone, and in his characteristic unpretentious, direct manner, he told the people he stood with them.

"I am Grandpa Wen. You will be rescued!" Wen yelled from atop the rubble. "The central government hasn't forgotten about this place. We will rescue those who are injured. If the roads are blocked, we'll use airplanes to lift them out."

For a nation long accustomed to political idols, Wen's spontaneous loyal following isn't something completely new. Mao's face may still dominate foreign perceptions of the CCP, but Wen reminds Chinese of a familiar past – Premier Zhou Enlai.

In times of political crisis, natural disasters, and economic restructuring the people of China heavily relied on Zhou Enlai for moral support and hope. Zhou Enlai was the founding premier of the People's Republic of China and became a strong image for Chinese citizens, as he made frequent visits to the country side which were documented in news reels and reported in newspapers. Wen Jiabao shares many similar parallels to Zhou, from his presence after the Sichuan earthquakes to his representation of the Chinese government as spokesman in response to the 2008 unrest in Tibet.

|

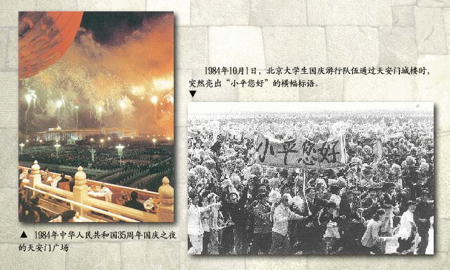

| “Xiaoping Ni hao” – a spontaneous expression of appreciation for Deng Xiaoping, 1984. |

|

| The website Kiss Baobao features a countdown until the 60th anniversary on October 1st. |

Wen’s following has developed in a far different social atmosphere than Zhou’s post-revolution years. In an age of new media and new networks, the Chinese public has found inventive ways to voice their support for the leadership.

Babaofan (

八宝饭)usually refers to “eight treasures rice pudding,” but admirers have creatively used the term to reference the popular Premier – the bao character is the same as in Wen Jiabao (温家宝), while fan (饭), or rice, is used phonetically as the English word “fan” i.e. fanatic. President Hu has a similar following – shijinfan (什锦饭), or rice pudding.

Taken together, Shijinbabaofan refers to all of the current Chinese leadership’s starry-eyed admirers. “Fantuan” (饭团), or rice balls, are individual fans. Shu Ze, founder of one Shijinbabaofan website (www.sjbbf.com), explained his motivation behind his online community. “My purpose is to gather the fans together and let President Hu and Premier Wen hear our voice,” Shu said. “I just wanted to provide a platform for the vast number of Shijinbabaofan to exchange and display their opinion on China's progress and the aspects of the things China needs to improve.”

While he’s long been supportive of China’s national leadership, Shu became focused on Wen and Hu after witnessing the problems that have arisen with China’s breakneck economic development.

“It was from the “San Nong problems” (三农问题) that I began to pay attention to the movements of state leaders,” Shu said. The San Nong problems, or Three Rural problems, refer to three negative developments of China’s modernization: income disparity between urban and rural dwellers, imbalance of coastal and interior development, and the inability to make money through agriculture.

While both men draw the admiration of millions, which one has the largest following?

“Absolutely Wen,” said Tan Xingye, a graduate student in international relations at Shanghai International Studies University “The impression is that Wen has a closer relationship to the public and is very diligent.”

As of July 21st, Wen’s Facebook page currently has 103,481 fans. Hu Jintao? Only 3,256.

You need to upgrade your Flash Player

Still, netizen Shiqing finds it hard to pick which leader is most deserving of his respect. “It’s hard to decide because I admire both of them,” he said. “If you really want to tell the difference, I would like to ask, who do you like better, your mom or dad?”

For a country once coerced into mass political idolization, the celebrity of today’s leaders represents something new. Wu Xinbo, professor of international political culture at Shanghai International Studies University, explained that while Mao’s cult of personality was often force-fed from the top down to the masses, Wen and Hu’s stardom has grown organically, aided in large measure by new communication technologies.

“Mao’s cult contained political tools and vocabulary – badges, quotations and slogans, dance, the involvement of politics in theatre, propaganda and so on,” Wu said. For today’s leadership, discussion of their popularity lies within “a [new] vocabulary, such as fans, Shijinbabaofan, Baobao, the Internet, the modern media, and animated images.”

"Mao's image is abstract, while Hu and Wen's images are concrete," Wu elaborated. "Mao has an abstract image of God, [something] unattainable and accepting of worship. Hu and Wen are more close to the public…they have the beautiful style [of being] on screen like movie stars." Wu added that historically, Chinese culture society has demanded a visible central leadership to maintain control within the nation. "Authority can be regarded as trees. If the tree falls, the monkeys will definitely scatter."

Wu explained that in the 1980s, as China opened to the outside world, a chaotic social situation developed. "Freedom became a new idol, the Western way of life became a new pursuit," he said. People delighted in being indifferent toward political figures."

Yet Chinese of that era were betraying their traditional roots. "Deep in their social psychology, people are still looking for anchorage, looking forward to the new authority," Wu said.

While there is no doubt that Mao and the current leadership's followings developed under different circumstances, perhaps the end result is nearly the same – a devoted and highly nationalistic public.

“At that time, there was a prevalence of personality worship and all the Chinese people revered Chairman Mao,” Tan said. “Now everyone likes Hu and Wen because of their own thoughts on their policies, not because of propaganda, but their individual subjective minds, which comes from their true feelings.”

While the online boom of supporters has arisen quickly and rather spontaneously, it has not been without some nurturing from the leaders themselves. In June 2008, President Hu joined netizens for a web chat, noting that “the Internet is a major channel to gather opinion and wisdom from the public.” In February 2009, Wen followed suit, discussing everything from economic stimulus plans to the shoe-throwing incident at Cambridge.

And Shijinbabaofan let the leaders know their feelings. Reminiscent of past student-led banner campaigns, Shu and two Fantuan put up two 10-square-meter posters on Wangfujing Street and Chang’an Avenue in central Beijing. The giant boards, emblazoned with a picture of Hu and Wen lighting the Olympic torch, had two sections –‘Shijinfan’ and ‘Babaofan.’ Faithful followers scribbled their names in a show of support for the leaders.

Peter Winter is a graduate student in Public Diplomacy at the University of Southern California. He is also deputy editor of US-China Today

.

Di Wu is a graduate student in Public Diplomacy at the University of Southern California. Her undergraduate work was at Tongji University in Shanghai, China.