The Chinese are Buying, Should We be Selling?

中国政府在投资买入,美国仍要继续卖出么?

The Chinese government's sovereign wealth funds, like those of oil-rich states, make some American officials, scholars, and investors nervous. Are these worries justified?

如同世界上石油储量丰富的国家一样,中国政府的主权财富基金让一些美国官员、学者和投资人感到担忧。然而这种担忧是必要的么?

by Lucas Rubio

Date Published: 10/24/2008

Chinese yuan is becoming increasingly important in the world economy. Photo courtesy of EETV.

What would you do with $200 billion?

Gao Xiqing, president of the Chinese sovereign wealth fund (SWF) China Investment Corporation (CIC) wrestles with this question every day. His recent investments include a US$3 billion stake in private quity giant the Blackstone Group (June 2007), a US$5 billion stake in Morgan Stanley (America's second largest investment bank, November 2007), and a more than US$100 million stake in Visa (the largest credit card firm, March 2008).

These are huge investments, but not as big as those of Abu Dhabi's SWF, which put US$7.5 billion into Citigroup in November 2007, and bought a US$800 million share of New York's Chrysler building this summer. By comparison, CIC is operating on a rather small budget, but its US$200 billion in a US$1.8 trillion dollar market has made enough of a splash to cause notice.

Even before the recent collapse of stock prices, the U.S. market was struggling under the effects of the subprime mortgage crisis and many welcomed the infusion of cash. Nonetheless some scholars and policy analysts are concerned that if this infusion becomes large enough to move financial markets, this power could be used for political ends.

The U.S. Department of the Treasury describes a SWF as a "government investment vehicle which is funded by foreign exchange assets, and which manages those assets separately from the official reserves of the monetary authorities." In other words, a SWF is a government-owned institutional investor. SWFs currently own an estimated US$3.5 trillion in assets worldwide, up from US$500 billion in 1990, and are currently growing at a rate of 24% a year. And as China's funds acquire stakes in more and more major foreign companies, some are getting nervous.

Source: Soverign Wealth Fund Institute

"We're dealing with very new phenomena," said Dr. Gal Luft, executive director of the Institute for the Analysis of Global Security, who testified on SWFs before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs in May 2008. "Up until about a year ago very few people even heard about SWFs, but because of the massive infusion of cash coming from countries like the U.S., Europe, the Asian and Middle Eastern countries, SWFs are gradually becoming a major player and are creating more wealth."

China's foreign exchange reserves totaled more than US$1.8 trillion as of June 2008, according to China's State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE). To help invest their funds in foreign markets China established the SAFE Investment Company in 1997 and most recently the CIC in 2007.

"China is not a free country," Luft said. "The economy is still controlled by the government. They don't have the free market system that the United States has, and the Chinese have a lot of cash to spare."

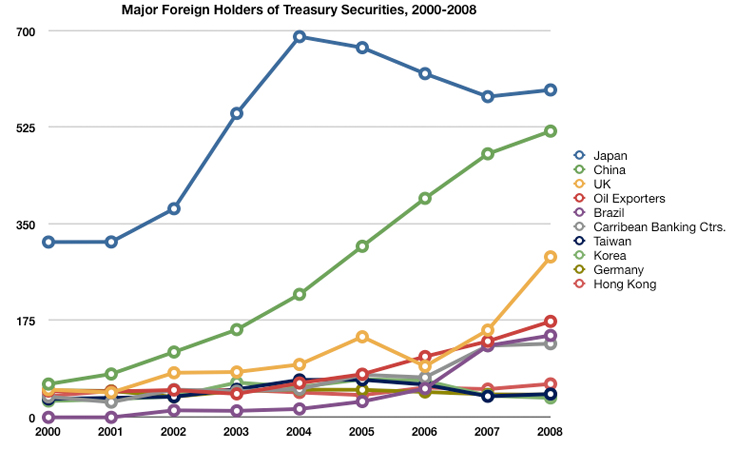

Though many argue China's market is increasingly free, there's no question that China's growing economy has generated unprecedented profits, largely held in state-controlled banks. Officials have traditionally invested in low-risk, low-yield government debt, especially American debt. U.S. Treasury bills, or T-bills, averaged a return of about 4-5% from 1998 to 2008, are practically risk-free, but are long-term investments of 20-30 years.

Prior to the creation of the CIC, China managed its foreign exchange reserves by issuing government bonds and then purchasing foreign government debt, primarily U.S. treasury bills. But the relatively low yield of such investments and the excessive concentration in a single investment has caused China's economic planners to begin looking for additional options (including mortage-based securities). So government money managers are now moving to buy shares in U.S. companies, investing in sectors like private equity.

"Countries like China don't need to hold any more T-bills," Kenneth Rogoff, former chief economist for the International Monetary Fund (IMF) told USA Today in June 2007. "There's just no point." By diversifying their investments, Chinese government money managers hope to increase their profits without taking greater risks.

"We'll ensure safety and liquidity while improving profitability of the country's foreign exchange reserves," Hu Xiaolian, administrator of theChinese State Administration of Foreign Exchange, told the China Daily.

The current financial meltdown is, naturally, making investors even more risk adverse, but even before the current crisis, Chinese government officials were worried about the cost of investing in "safe" U.S. debt. According to a Congressional Research Service report for Congress in January 2008, the appreciation of the Chinese yuan against the dollar has reduced the yuan value of dollar-denominated investments by by more than 10% since the beginning of 2007. To break even, then, dollar-denominated stock and bonds have to increase in value by 10%, and more, to turn a profit.

"The Chinese policy of managing their currency primarily against the dollar has meant that when the dollar falls China's own currency tends to fall," said Brad Setser, a fellow in geoeconomics at the Council on Foreign Relations. "As a result China tends to intervene more in the foreign exchange market when the dollar is under pressure then when the dollar is rising."

However, because of the lack of transparency of China's investment agencies, it is difficult for investors and government officials in the U.S. and elsewhere to evaluate and monitor their investments.

The Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute, a nonpartisan organization that studies SWFs and their impact, developed a transparency index that ranges from 0-10, with 10 being the ideal score. The SWFs of Norway and New Zealand—viewed as the highest standard in transparency—are rated 10. China's SAFE Investment Company and CIC are rated 2.

Click for graphs of the largest Soverign Wealth Funds and their transparancy. Source: Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute

"Unlike the SWFs of places like Norway that are highly transparent, the Chinese fall more on the side of Middle Eastern SWFs which do not offer transparency," Luft said. "It's hard to tell how their decisions are made and what their investment philosophy is, so everything is very speculative."

The supposed threat is that, through the financial markets, U.S. companies will lose their independence and necessarily serve the foreign policy interests of other countries. This fear builds on an assumption, as Luft puts it, "economic power often is translated into geopolitical power."

"China is purchasing an unprecedented amount of U.S. debt," Setser said. "Consequently, it's central to the process by which the U.S. government finances itself, central to the process through which the agencies raise money which they use to buy U.S. mortgages, and central to the overall financing of the U.S. external deficit."

The large sum available to the CIC coupled with the lack of transparency has caused some to raise red flags in a slowing U.S. economy.

Peter Navarro, professor of economics and political policy at University of California, Irvine, and author of The Coming China Wars: Where They Can Be Fought and How They Can Be Won, testified before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission that "China's SWF investments have contributed to the destruction of jobs and the slowing of economic growth in the U.S. because they are being accumulated and invested through the application of mercantilist trade practices that violate the norms of free trade."

According to Navarro, those violations include numerous World Trade Organization infringements, lax health and safety regulations, and currency manipulation.

"China manipulates currency," Navarro said. "The way they do that is they maintain a fixed peg with the dollar, and in order for them to maintain a fixed peg they have to recycle dollars back into the U.S."

Qualms over whether or not the Chinese government will use CIC investments for political ends are at the center of concerns about SWFs. At the same time China's investments in U.S. debt and corporations mean that China has a great stake in the overall health of the dollar and the U.S. economy. These investments in debt help keep U.S. inflation and interest rates low.

The CIC is also expected to permit diversification away from dollar denominated U.S. investements. To try to ease worries in the U.S. and elsewhere, CIC officials have stated that the company will not invest in politically sensitive sectors such as overseas airlines, telecommunications, infrastructure or oil companies.

On April 6, CBS broadcast a 60 Minutes interview with CIC president Gao Xiqing. Gao was grinning and, affable, telling correspondent Lesley Stahl that CIC will not intervene in the business decisions of the foreign companies they invest in, or obtain positions on their boards.

"It's our policy not to control anything," he said in that interview. "We don't want to go in and say, 'OK, I think you should change this person or I think you should change this product line. That's not our business."

Furthermore, the CIC, according to Gao, is taking stringent measures to become more transparent, something that has not been celebrated in Chinese culture.

"Our government has never been transparent for 5,000 years," Gao told the Financial Times. "Now we are told we need to be transparent and we are trying."

It remains unclear, though, exactly how CIC will make itself more transparent. The company is less than a year old and there is still American angst over the potential geopolitical power SWFs and their government masters might wield.

But one thing is clear—the U.S. and China are stuck with each other.

"Both economies are critical to each other," Luft said. "There is a strong interdependence—the Chinese need the U.S. market and the U.S. needs China's foreign exchange and investment. It's almost like two twins that depend on each other for survival."

Despite this acknowledged interdependence, or perhaps in light of it, there are calls for guidelines. There are already regulatory limits in the U.S. on foreign investment and ownership of certain industries, and major, potentially influential activity is subject to approval by federal regulators.

The calls resound internationally as well. Clay Lowery, U.S. Assistant Treasury's Secretary for International Affairs, called on the IMF and the World Bank to develop a set of guidelines for SWFs, and Congress adopted legislation in 2007 to help monitor and regulate foreign investment in the United States.

But according to Navarro, "regulation of SWFs through the IMF is not going to happen" because "it's not a practical solution to anything."

Navarro and others argue the many facets of the global financial marketplace require a more extensive framework to assess foreign investment in the U.S. and, in particular, to improve the transparency of SWFs like China's.

"Given how arbitrary the line is between central bank reserves and sovereign funds, how money can be moved from a sovereign fund to a state company, and how money from a central bank can be placed in a state banking system and lent to a state company, I think the review process has to be broader than one that just covers sovereign funds," Setser said.

Worries that China is trying to gain geopolitical advantage through foreign investment may be overblown. China's purchasing of foreign assets—on the surface at least—is part of the country's economic policy to diversify the government's investment portfolio and invest its resources more aggressively in order to improve earnings. It could be, as CIC preparatory group member Jesse Wang told the European Wall Street Journal, "purely investment-return driven."

"I think that in most voluntary transactions the buyer, or in this case the investor, and the seller, in this case the American company, both gain from the transaction or they wouldn't engage in it," said Charles Wolf, chairman in international economics and senior economic adviser for the Rand Corporation. "I think that is generally the case for Chinese investments in Blackstone, in Merrill [Lynch], and in CitiGroup."

Wolf continues, "I think it's important that these transactions be transparent, but with those two caveats-the one about defense related firms and the one about transparency—I think Chinese investments, Chinese acquisitions of shares in American companies are good for both them and us."

This is why many observers remain optimistic that the SWFs will yield positive results for the countries they serve and the foreign firms they invest in.

"By the end of the day what happens with SWFs is they invest through things like hedge funds and other mechanisms that are in themselves very transparent," Luft explained. "So there are multiple layers of regulation that needs take place, and the challenge is how to do it in a way that does not scare away foreign investors, because after all we would like to welcome investors, we just want to make sure it is done in a way that it is not detrimental to our economic sovereignty."

It is too soon to know the impact of China's SWFs. There is a clearly increasing trend toward interdependence, which is even more evident in SWF investments. Even those who anticipate positive outcomes, however, recognize the need for greater transparency on the part of the SWFs and attentiveness on the part of regulators.

Lucas Rubio is currently an undergraduate studying journalism at Santa Monica College.

|

"While we appreciate the long hours and the effort that our Chinese counterparts have put into those trade discussions, quite frankly, in the grand scheme of a $300- to $500-billion trade deficit, the things that have been achieved thus far are pretty small. I mean, they're not small if you're a company, maybe, that has seen some relief. But in terms of really getting at some of the fundamental elements behind why this imbalance exists, there's still a lot more work to do."

- Rex Tillerson, US Secretary of State, at a press conference during Pres. Trump's visit to Beijing, Nov. 9, 2017

|