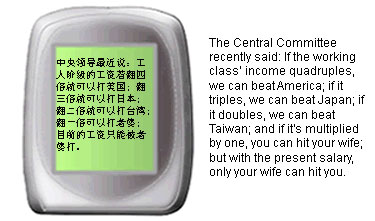

While American politicians worry about their political gaffes becoming fodder for countless blogs, Chinese officials are doing more than watching anxiously; they are cracking down. The fight, however, has been more difficult than anticipated. Why? Because these dissidents have a weapon even the Chinese government has trouble with: text messages—and often humorous ones at that.

Text messages have taken on a new purpose in China, quickly becoming the preferred mode of voicing public opinion. From jokes about current Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders to quips about the people’s thirst for money, text message-enabled cell phones have granted millions of people, especially younger generations, digital freedom of speech and access to information . Think digital “Suggestion Box” for a country that has never worried much about customer service.

Aysha {], a recent college graduate now living in Kashgar, Xinjiang, uses her phone to connect with friends across borders. A member of Xinjiang’s Uyghur minority group, she says texting has bridged gaps between ethnic groups in the region.

After texting a friend in Pakistan, Aysha [] said, “We all get along, especially the younger people.” She explained that texting is one of the only ways to stay in contact after the government changed migration restrictions in the northwest region.

2006 saw 449 million Chinese phone subscribers sending 392 billion text messages, or an average of 736,000 messages per minute. With broadcast capability, text messaging services allow a single user to reach thousands with a single click. Richard Baum, a UCLA political scientist, notes that the rise of new communication technologies, particularly cellphones and the Internet, have “exponentially increased the flow of spontaneous, unscripted and unsupervised information in China.”

This free flow of information has meant an increase in social activism, with Chinese taking up their cellphones to rally public support. In June, thousands of residents in Xiamen protested after receiving text messages warning that construction of a nearby chemical plant would bring environmental disaster. As a result, the project was delayed pending further environmental analysis, according to the Washington Post.

Cara Wallis, a Ph.D candidate at the USC Annenberg School for Communications, spent the past year in China researching the role new communication technologies have among the country’s migrant labor force. Wallis explained that much research has been done on more affluent, urban populations like Japan, where text messaging is seen simply as a supportive tool and relationships are maintained face-to-face.

“[In China,] I found the opposite. Because of work schedules, because of distances, [text messaging] becomes the primary means of sustaining one’s social network.

Wallis explained that migrant workers, because of social level and work conditions, often go months without a day off work. Moving from the countryside to cities, their mobile phones soon become a vital way to keep in touch with friends and family. Even dating has been forced to make the digital jump.

“It’s common to have relationships where the dating is all through text messages for months at a time before [the couple is] ever going to meet face-to-face.”

One reason for the growth in text messaging’s popularity is its cheap cost. Dennis Ding, a graduate student in economics at Peking University, said text messaging is a cheap alternative to ordinary phone calls.

“Making cellphone calls is kind of expensive here, especially in Beijing,” Ding said. “Since the telecom industry is monoplized by basically two mobile carriers, China Mobile and China Unicom, they are reluctant to lower the fees.”

At 0.15 yuan ($0.02US) per text, messaging services in China have experienced unprecedented expansion. However, the lines of communication are not without their limits. The New York Times reported in 2004 that the Chinese government began censoring text message services to prohibit talk about the Communist Party’s rule. China columnist Joseph Kahn said the tool’s widespread use in exposing the national cover-up of the SARS epidemic led to the decision. BBC News reported that, although the government took steps to conceal the disease’s outbreak, millions of text messages flooded mobile phones warning citizens to take precautions.

When asked about the government’s censorship of texts, Peking University student Ding said such restrictions do little to influence young people.

“No, people won't think about [censorship] when [they] are texting a message. [It is] hard to imagine how people can live if they think about it all the time,” Ding said.

But the Chinese government is taking forceful action, arresting dozens of “cyberdissidents” for posting messages deemed unacceptable to authorities. Beijing police issued a public notice in March warning mobile owners to not send pornographic messages. Users found guilty of misbehavior may be fined up to 3,000 yuan (US$388) and serve up to two weeks’ detention.

In 2005, thousands of Chinese took to the streets during a series of anti-Japanese protests. Organized by “chain letter” text messages, citizens were urged to boycott Japanese products. As reported by the International Herald Tribune, the Chinese government quickly banned texts containing anti-Japanese messages, fearing that such mass organization may later be used to mobilize anti-government protests.

Corporations are also finding the limits of their technological freedom. Baum, during a September 20th talk at the University of Southern California, detailed the situation of China’s largest blog host, Bokee.com. When Baum asked why the website voluntarily screens “offensive” subject matter, the company’s head responded, “We have a responsibility to our shareholders. If we allow anyone to publish sensitive content, the whole site will be blocked.”

SMS messages are just a piece of China’s information revolution and its ability to undermine authority. In 2005, famed filmmaker, Chen Kaige, sued Hu Ge, a small-town blooger, for making a satirical video of Chen’s The Promise, saying that Hu “has lost any sense of morality.”

Yet Chen’s legal actions, backed by the government, met an unexpected roadblock when thousands of netizens came to Hu’s support. The People’s Daily reported that Internet users criticized Chen as narrow-minded and petty, and the widespread criticism eventually forced the director to drop his lawsuit.

This is China’s new revolution. Citizens are turning to weblogs, text messages and YouTube-style videos to voice their opinions, often at the ruling CCP’s expense. With new technology, China’s virtual linkages are playing a critical role within society, allowing people to voice opinion and maintain distant relationships. Digital culture has led to social activism and new freedoms, and China’s citizens are embracing it all quickly, one text at a time.

Peter Winter is a junior majoring in International Relations and East Asian Languages and Cultures at the University of Southern California.