This text will be replaced by the flash music player.

|

When British-born DJ DSK was growing up, there weren’t any hip hop schools or Youtube rap videos. You had to bring your own sound. Now he, and surprisingly many like him, are bringing their beats to China.

“In China you have hip hop schools everywhere teaching B-boying, popping, DJ’ing. That's kind of crazy for me,” DSK said. “There is an exciting underground hip hop scene with some great talent ready to breakthrough.”

While 50 Cent and T.I. are staples of China’s club scene, underground artists like Sbazzo, Young Kin, and MC Ascension are creating new sounds in cities like Beijing and Shanghai.

DSK arrived in Asia in 1997, bouncing from country to country before settling in southwest China. His independent label, Unity Recordings, works to provide a platform for Chinese artists to produce “non-mainstream” music. The company recently released the first Chinese scratch record, providing local beats outside of the routine English-language samples while “for the first time, [allowing] Chinese DJs to give their routines and sets a genuinely Chinese flavor.”

“The scene in China is really split [between] MCs, DJs, B-boys and Graf (graffiti) writers,” DSK said. “As the younger generation get in more positions of income and power, there are more opportunities [in music and hip hop].”

Get the Flash Player to see this player.

From 说唱 shuochang (rap) to breakdancing to DJing, 嘻哈 xiha (hip hop) is catching fire among China’s youth. Foreign-born rappers brought the first sounds, but native Chinese talent is expanding the culture. Their jams have even hit the airwaves. The Park, China’s only hip hop radio show, broadcasts from Beijing, while Street Jamz is available across the country online. But what are they rapping about?

“The answer is everything,” said Angela Steele, a Fulbright Scholar studying Chinese hip hop. “Your life, your community, your neighborhood, what’s happening in your world. You’ll have an MC rapping about playing PS2, about the education system, about young love, topics across the board.”

Steele, who lived in Beijing last year, spent her time traveling across the country to study how hip hop is reshaping China’s music scene. Her blog, DongTing08, is a personal record of what she and research partner Lila Babb have discovered during their time with the country’s emerging artists. Steele has found that it is difficult to compare the U.S. scene with what is happening in China today.

“It’s interesting because we already have an idea of what hip hop should be. Any creative thing exists within a particular framework,” Steele said. “Do [Chinese rappers] have an explicit message in their music? Not really. This could be for the reason of self-censorship, the reality of government censorship…I think self-censorship is a bigger issue.”

|

|

Photo of DJ DSK. Photo by Metric1.

|

Movies like Wild Style, which showed the life of a young graffiti artist, first entered China in the mid-80s. More recent films like artist Eminem’s 8 Mile captured the style of freestyle rapping. While artists like DSK and others are not China’s first contact with hip hop culture, they may prove to be the most influential in furthering the underground scene.

“The scene in China is small but definitely growing,” said Wade Peng, an American breakdancer who studied at Shanghai’s Fudan University. “Dance studios and hip hop are growing in popularity, but it’s still limited to people who have the money to pay for classes.

Peng, a graduate of the University of California, Irvine, is one among many American foreign students who join hip hop dance teams during their time in China. “China is up and coming,” he said. “[But] it is still a Communist society…a lot of the media has been shut out for a long time.”

Right now it is impossible to pin down a uniquely Chinese style of hip hop. While foreign-born rappers first brought hip hop culture to China, the country’s homegrown groups and breakdancers are only now beginning to carve out their identities.

“The messages in the music are specific within their life and a Chinese audience,” Steele said. “It is too early to talk about a Chinese style. It hasn’t been around long enough to say there’s a style. Artists are individually developing individual styles.”

While many U.S. rappers are known for the political and social commentary that permeates their rhymes, Chinese artists operate in a much different environment. Jeremy Johnston of the rap group Yin Ts’ang put it clearly.

“I can tell you about what we don’t rap about: gangbanging, slaying coke, the government,” Johnston said. “That’s a good way to not continue your career.”

|

|

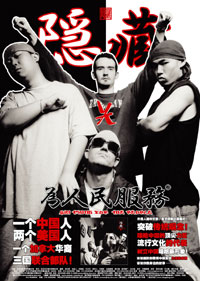

Yin Ts'ang.

|

Johnston, who grew up in Montgomery, Alabama, moved to China in the mid-90s. His group Yin Ts’ang is composed of one Chinese national, a Chinese-Canadian, and two Americans. The group’s first album, Serve the People, is considered by many to be the first Chinese rap album with mass appeal.

China’s rappers trade words in Mandarin, Cantonese, and even Uighur. They are from Shanghai, Beijing, Guangzhou, Urumqi, and Kunming. Johnston points to one of Yin Ts’ang’s upcoming songs, Wei Wo Zhi Ji Gan, or “Do It For Yourself,” as an example of their lyrical style.

“It’s a commentary that you gotta work so hard and in the end you gotta be happy with what you did,” Johnston said. “This is hip hop and that’s what hip hop is about. It’s doing things to make yourself better. In the end, community is about self. If you aren’t happy with yourself you can’t help other people.”

But even friends have differences in opinion. Andreas Hwang, a.k.a. Young Kin, founded the independent label YinEnt with Johnston. The rapper takes a decidedly more political approach to his words.

“I do also get political. I’m not afraid of that,” said Hwang. “If I was a Chinese national, I would be afraid of that, but I’m not. I’m not saying “down with the government”…I’m just saying there are a few problems here…It matters what freedom you give your people.”

Hwang, who was born in Switzerland but moved to China as an infant, noted that in recent years, especially in the run up to the 2008 Olympics, his rapping took on a more socially conscious angle. A local radio station refused to play one recent track, “为什么” or “Why,” because of its commentary on China’s one-child policy, ethnic minority issues, and social freedoms:

Government pressure influences China’s artists and limits their lyrical freedom; however there is room to explore some of the country’s more controversial subjects without bringing political heat. “Unique II” by Shenyang rapper FK Moses hits on the hardships faced by young migrants who leave their hometowns in search of better lives in the cities. Jia Wei of In3 raps about the pressures of ordinary society and music’s liberating ability in “Freestyle.”

Dumdue is one of the most prominent rap groups in Guangzhou. Their music combines jazz with elements of traditional Cantonese music. In an interview with DongTing, KidGod described the group’s music as more socially conscious than some realize. “A lot of it is about problems in society. It is dark. Our way of thinking is kind of dark.”

Get the Flash Player to see this player.

Steele adds that, many people ask her, as a scholar, about the possible political impact of hip hop in China, especially given the art form’s rebellious nature. She thinks that the Chinese situation is developing a bit differently.

“I guess the fact that people ask the same questions mean that people think that hip hop should work a certain way in another country. I would just encourage for people to go further and accept something that we’re not used to in the U.S.”

Following a recent New York Times article on the subject, some artists and bloggers took issue with assertions that China’s hip hop movement is having a large impact on mainstream society. Steele wrote that “Most rap music in China does not have a political agenda” and is largely “being made by young kids who have no context or understanding of Hip Hop culture and can only emulate the posturing, style and attitude of popular…artists.” One blogger wrote, based on his experience, that “the angry Chinese rap I’ve heard is generalized teenage angst with no attempt at social commentary. The most “daring” rap I’ve heard is predicated on schoolboy puns about smoking pot.”

But rather than it being a cohesive movement with a political message, China’s hip hop community is bound by individual identities, experiences, and struggles that are relatable through an appreciation for an alternative musical style. While socially conscious lyrics do seep out, interpretations of a coming political revolution may be premature. Hip hop’s impact may not come in the form of mass demonstration, but rather its challenge to certain social values and traditions.

“I don’t want anarchy,” Hwang said. “I’m just after some justice and I think that’s what most people in China are after.”

While rap music has stretched across the global stage, its most visible roots lie in the United States. For young Chinese fans, their views of the U.S. and its people can be greatly influenced by the words and images of American hip hop culture.

Johnston explained that, as a white rapper in China, a different set of rules applied while he was coming up. “On the one hand, there’s a lot of more commercial-type gigs that would like to have a foreign monkey boy on,” Johnston said. “People would say, “Oh you’re white. White people can’t rap.” He noted, however, that it still comes down to ability in China. “Skills always speak for themselves…People are going to have their own mentality whether you want them to have it or not. All you can do is grind it out.”

“The racialism of China is completely different,” Steele added. “I did get this idea that attaches blackness to legitimacy and that if you could make your hip hop more black, [it would be better]. I heard, “We need to make this song more hei” (黑, black).

Some critics of hip hop view the art as negatively reinforcing stereotypes about African-Americans, a charge that even applies in China. Steele noted that music can play an important role in developing cross-cultural understanding.

“Some of the hip hoppers, some of those that know the most about the black experience, use hip hop as a springboard to learn more about black Americans to combat stereotypes, as opposed to others who simply intake images of stereotypes.”

While racial tension and social rebellion were integral to the development of hip hop in America, those play much smaller roles in Chinese hip hop given China’s much different social-economic and political history. While some in China view non-black artists and sounds in Chinese hip-hop with skepticism, as the genre grows and more local artists emerge, the Chinese hip hop scene will develop its own distinct and legitimate style separate from that of American hip hop.

|

|

Photo by Shazari.

|

Hwang explained that while China’s earliest rappers came from abroad, the hip hop scene now belongs to domestic talent.

“It used to be all foreigners, now Chinese hip hop is mostly Chinese,” Hwang said. “It first started off as an imitation but now things are getting their own shape.”

While Chinese rappers are emerging, the mainstream viability of rap in China still depends on its ability to draw attention from the home audience. “The thing is is that it’s still foreigners that are more interested,” Johnston added. “It’s still too foreign of a culture, too foreign of a concept for them to get into. [But,] that’s what we’re here to break down…to get local people, the local Tom, Dick, and Harry to at least get an understanding of what hip hop in the streets represents.”

FK Moses and Dumdue might not be household names in China, but mainstream pop stars like Wang Leehom and Jay Chou garner the country’s attention. Some of their songs, like Wang’s “Not Your Average Thug,” have a decidedly American hip hop influence, creating greater interest among China’s youth.

Johnston, however, doesn’t approve of the current commercialization of rap in Chinese popular music. “What I don’t appreciate is that they aren’t helping the next generation. They aren’t in it for the culture but for their own pockets,” he said. They’re using hip hop to make money without helping hip hop. They’re not helping the hip hop community that’s writing songs and freestyling.”

“There are no rappers living off of hip hop in China,” Steele added. “Some rappers have day jobs, some have no jobs, some live with their parents…Are they going to enter hip hop full time knowing that they won’t be making too much money or are they going to work full time knowing that hip hop would become a side hobby because they have to live.”

For artists like Johnston, Hwang, and DSK, hip hop is an expanding culture, not just a way to make money. The movement lies in the community of hip hop artists, their lifestyle, and their individual voices.

“We’re approaching retirement, and we just want to set it up so that the next generation doesn’t have to go through the [problems] we went through,” Johnston said. “But now people are listening to hip hop, not just hip hop, but Chinese hip hop. When we got here, no one knew what that was.”

“Maybe five to ten years, it’s going to be really big,” Hwang added. “Everyone knows the market is huge. The question is how do we crack it?”

“Everything is in place except for that breakthrough moment,” Johnston explained. “We haven’t had the Run-DMC “My Adidas” track on the radio yet to open up the floodgates for the other hip hop artists to get on.”

That breakthrough moment might just be coming.

Jonathan Hwang is a senior studying International Studies at the University of California, Irvine.

Peter Winter contributed to this article.