Shanghai’s Nanjing East Road glitters with signs and storefronts of globally recognized brands Louis Vuitton, Chanel, Dior, and other luxury labels. Such names were nearly unheard of in China as recently as three decades ago. As the number of affluent Chinese increases, these companies have energetically sought to win them over.

McDonald’s and Starbucks outlets have become commonplace, but these companies are selling goods that are too expensive for the average consumer, indicating that there is more than sufficient demand in China for them. In the country’s various metropolitan hubs, boutique stores carrying the names of these globally recognized brands are becoming increasingly visible.

These retailers are looking to China to help them counter stagnating sales in other markets—namely Europe, the United States, and Japan. While plans for expansion have been put on hold in these regions, labels such as Hermes plan to add another three to four stores in China in the near future. Versace expects China to become its second largest market, surpassing the United States by 2009, according to a report produced by China Market Research Group.

Anticipating luxury goods to become the next hot market in China, companies are employing tailored strategies to stand out amongst a sea of competing brands and appeal to the aspiring Chinese consumer. Although China may have a GDP roughly one-sixth that of the United States, there is still huge demand for luxury items from the affluent elite of Chinese society.

“Although China's GDP per capita is about US$1,000 and still very low compared to the US, the absolute number of rich and affluent consumers still number more than 200 million,” said Pierre Xiao Lu, assistant professor of marketing in Shanghai Fudan University and consultant for various multinational luxury firms.

In his book Elite China: Luxury Consumer Behavior in China, he differentiates between various economic classes belonging to the “rich and affluent” group. Because Chinese households have more spending power per dollar than their counterparts in developed countries, the lowest threshold for this group is US$14,000. The upper limit, of course, includes China’s billionaires. Lu continues, “[This] means that luxury goods are not for everybody but [those] who can afford [them]. It is never a mass market product for the average consumer.”

|

|

|

Many of these individuals belong to a burgeoning class of wealthy businessmen and professionals, created by the onset of China’s economic reforms. Being able to afford goods from such prestigious labels represents personal success and achievement.

Even if one cannot afford them, he or she can still aspire to own such goods. A luxury retail report by consulting firm KPMG China argues that purchasing luxury goods also strikes an optimistic tone: one is confident about one’s personal financial future.

Companies have found that Chinese consumers are different from Western or Japanese ones. Marketers for these companies believe many Chinese consumers see luxury brands not just symbolizing their social status, but also as expressing their personal style. Chinese consumers are becoming more aware of brands and their histories, stories, and ethos.

As Jessica Lo of China Market Research Group puts it, “Because the cost of home ownership or car ownership may be out of reach for many consumers in China, they will often make expensive purchases of luxury goods that they get utility from. Expensive mobile phones, or bags and wallets that can be carried and displayed frequently are examples of purchases that consumers are willing to spend a large percentage of disposable income on.”

Although the West has strong influence on the Chinese consumer, Chinese consumers are continuing to develop their own barometer for what is considered aesthetically acceptable and sophisticated. The result is, according to consultants Radha Chadha and Paul Husband, authors of The Cult of the Luxury Brand: Inside Asia’s Love Affair with Luxury, “taste is not part of the equation—conspicuous consumption is an end in itself. The more you spend and the more you flash the cash, the higher your status in society.”

Because luxury brands serve the purpose of conveying wealth and status, consumers rank brands based on how expensive they are. This is an important point for luxury good retailers to consider when thinking about what they want to emphasize about their brand.

How do such characteristics of the Chinese market figure into the marketing strategies of luxury retailers? With a fledgling market like China’s, now is a great time for companies to develop brand loyalty among the Chinese market, says Lo. She goes on to state, “Chinese consumers are still learning about and differentiating between brands as they try to determine what fits their sense of self.”

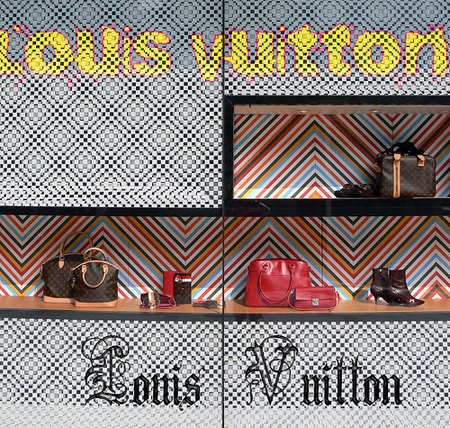

Building brand recognition is an essential component of a luxury good company’s strategy in China. The simultaneous influx of foreign companies may seem non-differentiable to the aspiring Chinese consumer looking to spend disposable income on luxury goods. Hence, they rely largely on visual cues, according to Lo, such as being able to distinguish the Louis Vuitton label by their patterned fabric, or recognizing the white star that is a Mont Blanc trademark.

Also, says Chadha and Husband, because many consumers in China are not fluent in English, “logos and symbols…become mission-critical visual shorthand in China. Consumers often refer to brands by their initials—CD and DG are after all a lot easier to master than Christian Dior and Dolce & Gabbana.” Such a strategy is important in a market where an individual is still in the process of educating himself or herself about various brands and deciding which ones will fit best with their own personal sense of style.

Another issue for foreign luxury good companies to be aware of is harmonizing their label to make it relevant to the Chinese consumer. A company, for example, will be more appealing if it can capture local cultural elements and incorporate them into their advertising campaign. In other words, marketing tactics that may work in Western markets may not in China.

A market research report recently released by KPMG China cited Louis Vuitton’s distribution of Chinese lantern charms to mark the opening of its new store in Beijing. Lo also named BMW as a company which understands the importance of incorporating local values in its advertising tactics. The company launched a television ad campaign that “highlight[ed] the concepts of respect as well as personal mettle.” Such ideals “play into the concept of generational respect but also give room for the concepts of optimism and self reliance that are important to aspiring consumers.”

Get the Flash Player to see this player.

As the luxury market becomes increasingly saturated, it gets harder for firms to differentiate themselves from other brands. Lu says, “For relatively less-known brands looking to enter the Chinese market now the risk is very low, but they have to face the very difficult situation of making their brands famous. [Firms] have to pay much higher market entrance fees to firstly learn the market, [and] secondly to do branding and pay higher rental fees to find a perfect location for their stores.”

In order to successfully break into the market, he continues, the first step is to educate the Chinese consumer about the brand’s history and principles. Lu highlights the important market strategy of initially “us[ing] the international communication strategy to build a strong brand and to tell your brand DNA and core values to Chinese consumer, to tell them who you are and where you come from.”

The next step is to “integrate more Chinese values [in a brand’s communication strategy]…in order to decrease the psychological gap between the brand image and local consumers.” Lu cites several examples of firms successfully undertaking this task—Louis Vuitton inviting well-known Chinese model Du Juan to be the face of their international advertising campaign, and Zegna, which used images of the Chinese landscape as part of their own campaign in 2008.

The localization of foreign labels is an indication of the deep investment many firms have made in their forecasts that China will become the next major market for luxury sales in the long term. As Lu explains, “Most luxury brands realize that it is the right moment to continue their investment in China market in order to benefit from the strong domestic demand for luxury goods and compensate for the sales decrease in the U.S., Japan, and Europe…from the long term vision, it is an absolute step to increase the investment in the mainland.”

Brandy Au is a graduate student in the Politics and International Relations Program at the University of Southern California.

Top photo by Sea Mang and used with permission.