The cheers were deafening.

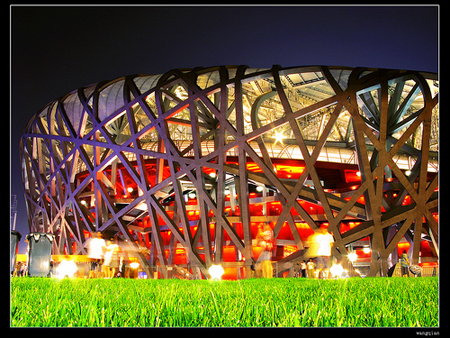

Red and gold flags enveloped the Bird’s Nest as Chinese sprinter Liu Xiang lined up for the 110-meter hurdles. The poster boy of the country’s Olympic hopes, Liu had become more than a runner since his success in Athens four years earlier—he was the athletic face of New China, a strong and renewed nation ready to take its place on the world stage. Painted from head to toe in their homeland’s colors, his fans watched with burning anticipation as the "Flying Man" prepared for takeoff. The crack of the starting pistol…

The silence was heartbreaking.

Liu was injured, his hamstring unwilling to permit him to continue. As he limped away from the line, the stadium grew quiet, fans looking on as an Olympic dream died on the blocks.

One CCTV broadcaster wept as she delivered news of Liu’s injury to her countrymen. Sun Haiping, the runner’s coach, sobbed uncontrollably during a post-race press conference, his emotions symbolic of national sentiment. The blow hit China hard--a tremendous blow to their Olympic success.

"Despite the fact that China won 51 gold medals at this year's Olympic Games, [without] a gold medal from Liu Xiang, the picture is definitely not perfect," said Xu Guoqi, author of Olympic Dreams: China and Sports, 1895-2008. "[Liu] represents everything Chinese want to convey to the world: confidence, a can-do spirit and forward-looking. When Liu withdrew from the event, most Chinese were devastated."

Even China’s top leaders were quick to comment on the national implications of Liu’s race. Vice President Xi Jinping penned a letter to China’s General Sports Administration, expressing his condolences.

"We all understand that Liu quit the race due to injury," Xi wrote. "We hope he will relax and focus on recovery. We hope that after he recovers, he will continue to train hard and struggle harder for the national glory."

Beijing National Olympic Stadium (Bird's Nest). Photo by Wang Qian. Creative Commons license.

The fervor surrounding Liu’s run had become commonplace in the run up to the August Games. As the country embraces its newfound status in international society, a national pride has grown among the public. With decades of economic prosperity, the country’s rise has been mesmerizing, astounding even the fiercest critics.

J. H. Santana Wulsin, an American expatriate now working in Beijing, found the wave of "China Pride" captivating.

"In restaurants, subways and offices--everywhere--there were groups of enthusiastic Chinese watching the Games, cheering wildly for the good and sighing with resignation for the bad," he said. "The events truly did consume every waking moment of the entire city."

Recent surveys conducted by the Pew Global Attitudes Project prior to the Games found nearly that 96% of Chinese believed the Olympics would be an overwhelming success, helping to strengthen China’s image around the world.

In the months prior to the Games, however, the enormity of that pride unsettled some foreign onlookers, troubled by the prospect of fervent nationalism driving China’s policies toward other countries.

"The legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party is based on three legs: economic growth, nationalism and social stability," Xu said. "Unfortunately, these three legs are not completely compatible. To stay in power, the Party has to be champions of nationalism. But the rise of nationalism can be a double-edged sword which can hurt the party as well if the rise of nationalism leads to social unrest or negatively influences Sino-foreign relations."

Provoking nationalism for political support is nothing new. Politicians, including Chinese ones, have long appealed to their people’s sense of self to garner support for policies. The extent, however, to which China’s nationalist furor erupted in recent months has become the primary concern.

The reaction to riots in and near Tibet earlier this year provided a glimpse into this dark side of nationalism. Chinese television audiences did not see and were not told that the initial protests were peaceful ones. Instead, they only saw images of Tibetans violently clashing with security forces. When international leaders and organizations condemned the conditions that provoked the initial protests and urged the Chinese government to act with restraint, many Chinese were outraged. They attacked news organizations as biased. State-run news sources inundated the Internet with their side of the Tibetan story. Xinhua hosted one website featuring videos, commentary, pictures and articles on the ruthlessness of the Tibetan movement, China’s economic development of the region and biased foreign media reports. Chinese netizens took to online discussion boards, condemning foreign intervention in national affairs. The song, "Don’t be Too CNN" by Murong Xuan, became a popular hit by lampooning CNN and other international media for what they saw as false reports.

At Duke University, Chinese student Grace Wang stood between pro-China and pro-Tibet protest groups and called for dialogue and understanding. The next day, an image of Wang appeared on Chinese student Internet forums with the words, "Traitor to your country," emblazoned in Chinese across her forehead. Wang’s name, government issued-identification number and contact information were included, along with directions to her parents’ apartment in Qingdao. One netizen threatened, "If you return to China, your dead corpse will be chopped into ten thousand pieces."

Chinese foreign students showing their national pride for the Olympics. Photo by Kordan Wooley.

Suisheng Zhao, director of the Center for China-U.S. Cooperation at the University of Denver, explained in a recent article that China’s hosting of the Olympics has brought a certain amount of unexpected attention to the country.

"The 2008 Summer Olympic Games in Beijing have brought not only the celebration but also intense international scrutiny of China’s weaknesses," he said. "The scrutiny has focused on many of China’s domestic and external challenges, including pollution, human rights, media freedoms, along with the issues of Tibet and Taiwan."

This oversight has fueled the Chinese nationalist response, highlighted at each stop of the Olympic torch relay. Chinese students studying in the United States mobilized to support their government and the Olympics, turning out at the torch relay stop in San Francisco and at an anti-CNN rally outside the network’s Los Angeles offices.

Following massive protests in Paris, London, San Francisco and New Delhi, outraged Chinese citizens took to the streets, angered by the perceived foreign malevolence. After protesters in Paris assailed Chinese Paralympic fencer Jin Jing during her leg of the torch relay, a mob in Qingdao gathered outside the French-owned supermarket Carrefour, burning French flags and calling for a boycott of foreign goods. During the South Korean leg of the relay, thousands of Chinese foreign students gathered on the streets of Seoul. Reports of several clashes between the students and pro-Tibet elements soon followed.

Daniel Bell, professor of philosophy at Tsinghua University, explains that the Chinese reaction has largely been a response to one-sided Western attitudes.

"The international protests during the torch relay were partly, if not mainly, the product of the dominant Western response to the Tibet riots," Bell said. "The riots [in Tibet] targeted Chinese civilians at random, and most Chinese were genuinely puzzled by the surge in sympathy for the Tibetan cause and apparent lack of sympathy for the Chinese victims [killed or injured during the rioting] in the West."

Bell notes that the Chinese public’s understanding of the situation in Tibet is perhaps deeper than many Western viewers believe.

"I think most educated Chinese are aware that there are repressive policies in Tibet, and many Chinese students were upset at tightened Internet controls after the riots, but they were still puzzled by the dominant response in the West," he explained. "It should also be said that Chinese students abroad are often more jingoistic than the ones in China. In China, they are often critical of their own government, but they become more defensive when faced with criticisms by ill-informed outsiders."

The Beijing Games has also fueled extreme reactions from others in the region, bringing out fringe groups to protest the country’s host status. In Nagano, Japan, ultra-nationalists crowded onto streets, blasting messages of hate across loudspeakers. According to the Times Online, Japan’s nationalists have used the pretext of the Tibetan crackdown to push their anti-China message. Reporter Leo Lewis captured the scene:

"China is not qualified to hold a festival of peace because it is a country that murdered Tibetans," one protestor shouted. "We must establish a true national army to protect against China," another screamed.

Opening ceremony at the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Photo by Dennis Collette.

The unpredictability of a nationalist public has aroused concern in the Chinese government. Its immediate and potential long-term effect on foreign relations clearly apparent, the Communist Party now worries about its consequences at home.

"Although the Chinese government has relied on nationalism to bolster support since communism disappeared as a unifying principle, expressions of strong nationalist sentiment can also lead to protests against the communist government," Zhao writes. "The increasing assertiveness of popular nationalism has thus posed a daunting challenge to a communist government clinging to its monopoly on power."

Still, the benefit of nationalism as a legitimizing force for the Communist Party is not unappreciated.

"Despite its lip services to nationalism, the government so far has been largely passive responding to events," Xu said of the CCP’s reaction to outbursts of nationalism. "External pull, not internal push, explains the Chinese government's behavior pattern."

Xu, however, does not dismiss the importance of keeping nationalism under check.

"Of course, the government has to also pay delicate attention to domestic public opinion," he said. "After all, it is the Chinese people who can take the mandate of heaven away from the Party."

Xu said that the government was effective, however, in suppressing any overtly nationalist outpourings during the Games.

"Although Beijing hosted a quite impressive Games, it succeeded at the cost of stealing fun away from regular citizens in the name of security. There were no public and spontaneous [large-scale] celebrations or rallies, which took place regularly in the past," Xu said, highlighting the effect such events might have on foreign opinion. "A possible reason for the government to discourage average Chinese from public gathering is to prevent any possible impression of the rise of Chinese nationalism to the rest of the world."

Bell is hopeful about China’s continued development following the Olympics.

"My impression is that the games have been widely [regarded] as successful in China," Bell said. "The relatively civil Olympics should have improved U.S. perceptions. Predictions of jingoistic nationalism during the Olympics proved to be wrong."

Bell concludes that while Beijing’s need for a successful Olympic Games did create somewhat artificial social and political controls, he expects the broad trend towards openness in Chinese society to continue.

"In a way, the Western governments and human rights groups that expected the Olympics, per se, to bring out openness had it backwards," he said. "For the Chinese government, and I think there was substantial popular support for this view, the overriding priority was to secure a stable social and political environment during the Olympics, but there will likely be more pressure for opening up social and political debate after the Olympics."

Peter Winter is a graduate student in Public Diplomacy at the USC Annenberg School for Communication. He is deputy editor of US-China Today.