China is the world's heaviest smoker. The China National Tobacco Company (CNTC), a constituent of the government-run China State Tobacco Monopoly Administration, is the largest tobacco company in the world, and Chinese constitute one-third of all the world's smokers. Also, the country's tobacco industry accounts for about 8% of total government revenues, according to the World Bank, and health experts and global economists are curious: Can the Chinese government kick the habit?

Hu Teh-wei, professor of health economics at the School of Public Health at the University of California, Berkeley, says it can. In his 2008 report on tobacco control in China, titled, "Raise Tobacco Tax, Save Lives," Hu rebukes previous arguments that raising the tobacco tax in China would contribute to a loss in total revenue for the China State Tobacco Monopoly Administration (CSTMA).

"We have convinced the minister of finance, the minister of health, and so on, that tobacco control is a win-win policy," Hu said. "That means it will not only reduce cigarette smoking's present rate, it could also reduce consumption, but actually raising [the] tax will increase revenue." 2008 revenue was 430 billion yuan.

You need to upgrade your Flash Player

The report, which is supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Bloomberg Foundation, proposes a tax increase of 1 yuan (about US$0.15) per pack of cigarettes (which average about 5 yuan, less that US$1), which would presumably save more than 13 million lives and generate around US$9.5 billion in additional revenue.

China's current 40% tobacco tax (calculated as 40% of the total retail price) is considerably lower than in other countries, which average about 65%. Experts say the Chinese government has been reluctant to raise the tobacco tax because the increase could threaten not only revenue for the CNTC, but also the estimated 4 million Chinese who work either on farms or in factories and rely on the tobacco industry for their livelihood.

Gary Hufbauer, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics whose expertise is in tax and trade policy, says that the Chinese government can indeed increase CNTC's revenue by raising the tobacco tax, but they can not simultaneously save lives in the process.

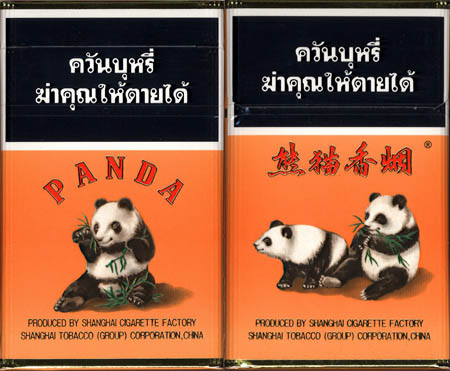

Cigarettes can easily be bought in shops like this all over China. Photo by: Chase Tingley

"The question is whether the increase in taxes reduces smoking in percentage terms more than the percentage increase in taxes," he said, "and certainly in the short run it does not.

"Maybe over a long period of time, like a decade, you might have that effect," he continued, "but I know within the first, say, three to five years, you will not reduce the smoking as much as the percentage increase in the tax. Therefore, the total revenue collected by the government will go up, if you include the tax in the revenue."

There are around 350 million smokers in China, and every year about 1 million of them die from tobacco related illnesses, including emphysema, lung cancer and chronic bronchitis, according to the World Health Organization. This amounts to roughly 186 billion yuan in ecnomic losses every year, or 1.9% of GDP, and the death toll is expected to double by 2020 if the trend continues. In addition, experts estimate that about 540 million Chinese citizens are exposed to second-hand smoke each year, resulting in 100,000 deaths, with premature deaths related to smoking expected to exceed 2 million annually by 2020.

Though about 8% of the government's annual revenue comes from the industry, Chinese and international health officials are striving to impose more stringent tobacco controls in China, as well as raise the awareness of the dangers of smoking and second-hand smoke. However, opposition is strong.

The smoking rate in China among males is about 70%. The rate for women, which in recent years remained consistently at 3 to 4%, is now eking up to 10% in some provinces, according to an ongoing study by the USC Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Research Center, or TTURC.

"I think it's going to be really hard to change behavior," said Paula Palmer, assistant director of TTURC and director of Global Development at the Institute for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research at the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California. "Tobacco use there is really a right of passage for males," she said. "It's the gift that people give."

According to Palmer, the Chinese government has been passive when it comes to promoting the dangers of smoking and second-hand smoke.

Photo by: hakaider

"You know, they refine and ratify the FCTC," she said, referring to the Chinese government's work on the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, a global public health treaty to stop the negative health and economic impacts of tobacco, "but in terms of actual cessation programs, there really aren't any in China. In terms of prevention programs, we have one of the only ones currently under development," she said, referring to the Chengdu Smoking Prevention Program for Chinese Adolescents.

"So the public mouth is talking about how much they're doing, but in terms of what's really happening internally and at the city levels, not much is happening.

"And we know that they're in the race for the big bucks," she added.

Between January and November in 2008, CNTC produced more than 42 million cartons of cigarettes, an increase of more than 2 million boxes from the same period last year, and contributed nearly US$63 billion in taxes, according to The People's Daily (Renmin Ribao). In addition, CNTC has been involved in a joint venture with Phillip Morris International since 2006.

"We believe that smokers should continue to know about the dangers of smoking and that governments must take the lead in communicating about the health risks of smoking," Monica Montero, a spokeswoman for Phillip Morris International, wrote in an e-mail message. "We support a clear and consistent public health message about smoking, disease and addiction wherever we sell our products."

Phillip Morris International refused to comment on their business operations in China.

The Chinese government, though, has already made moves to crank up tobacco production. Jiang Chengkang, a CSTMA official, issued a statement in December confirming that the government was investing 40 billion yuan (US$5.84 billion) in tobacco farming with hopes to increase their acreage by 2.33 million hectares.

The decision came a month before trade tariffs were to be lifted in China, which allows foreign cigarette brands a stronger presence, increasing the total market share and creating more competition for Chinese domestic cigarettes. Popular Chinese brands include Happy New Year, Red Double Happiness, and Temple of Heaven, and cost around US$1.

Moreover, analysts expect the invasion of foreign cigarette companies to swell the already robust Chinese market with influential tobacco advertising, and some even fear that foreign companies may try to gain leverage at the governmental level.

The Western cigarette company British American Tobacco was pilloried in December when a report published in the online medical journal, PLoS Medicine, suggested that the company trained CSTMA officials to understate the risks of second-hand smoke during what the company called "smoking and health seminars."

Although BAT denied any wrongdoing, the paper reinforced suspicions that the Chinese government is reluctant to make substantial changes to the country's tobacco control policy because the government is afraid of losing revenue from the CNTC.

"From the cigarette industry point of view, either domestic or foreign products, if the smokers continue to smoke that will help them," Hu Teh-wei of the University of California, Berkeley said. "But from our tobacco control policy point of view, that's not good news."

Many analysts agree that the future of China's tobacco industry is either "economics or health," not both. And it seems that for now, the economy is winning, and the only warning most smokers will see is the feeble message on cigarette labels: "smoking is harmful to your health."

Lucas Rubio is currently an undergraduate studying journalism at Santa Monica College.