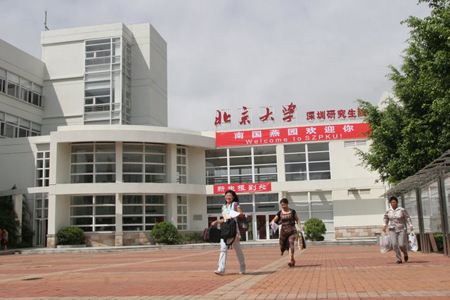

New students registering in September 2008.

In China, anyone with a university degree can sit for the bar exam and be eligible to practice law. But now, one of China's most distinguished universities is giving Chinese students the chance to earn a more coveted license: an American law degree, without leaving home.

When it opened its doors in August 2008 with 56 students, the Peking University School of Transnational Law (STL) became the first of China's more than 600 law schools to prepare its students to receive a Juris Doctorate. All the classes are conducted by high quality professors in an English setting.

"What we are trying to do is nurture a set of intellectual skills that have been nurtured within American law schools primarily but to do it in a Chinese context," said Jeffrey Lehman, Dean of STL. "People describe what we're doing as American legal education with Chinese characteristics."

Lehman's resume includes being a former dean of the University of Michigan Law, President of Cornell University, and former law clerk to U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice John Paul Stevens. Given Lehman's track record, it was no surprise why he was tapped by Peking University Vice President Hai Wen to create STL.

STL represents a stepping stone in the development of China's legal education. It's the first university in China to offer an American style J.D. But more than that, STL is proof that the practice of law is becoming more globalized. It transcends national boundaries to the point that American and Chinese lawyers both speak the same language -- legalese.

|

|

2008 STL students during Orientation Week.

|

Currently, out of more than 200 applicants, 54 students are enrolled (two enrolled students dropped out for family reasons). The class has slightly more women than men, and all are from mainland China. But this doesn't mean foreign students aren't welcome.

"In 2009, we will have four international students— two of them will be from America," said Chenli Zhang, director of student affairs.

By Chinese standards, tuition is a bit pricey at 120,000 RMB (about US$17,600), making STL over ten times more expensive than the average Chinese law school. "Law school tuition and fees in China is similar to other college disciplines," said Sida Liu, a recent PhD in Sociology from the University of Chicago and an expert on China's legal profession "It varies from university to university...but the annual tuition even today should still be below 10,000 Yuan around maybe 1500 US,"

However, there is help available. "We provide scholarships on a large scale," Zhang added. "More than 30% of students can apply for scholarships. Most of them apply for commercial aid from banks and other financial companies. STL and Shenzhen Graduate School contacted several banks, including Bank of China, small city banks, and China rural commercial banks like Merchandise Bank in China."

But the currently enrolled students are taking a gamble— the school isn't accredited just yet. However, as early as the fall of 2010, the school can apply to become provisionally accredited by the American Bar Association (ABA). But this is not an easy task, and no school outside the U.S. has been awarded accreditation; no school has ever tried. Presumably this is because there are plenty of law schools in the U.S. who welcome strong international students. However, Peking University's decision to open STL reflects a growing awareness of the need for lawyers who can meet the demands of multinational law firms and companies, including those in China.

"People are properly skeptical about whether a brand new school in China has the staying power, the determination, and ability to make it through the process," Lehman said. "As of today, we are not in compliance with all of the standards. We're still hiring faculty and depend heavily on visiting overseas professors."

But the payoff for STL is that upon receiving provisional approval, students graduating from a provisionally recognized school would be eligible to take the bar exam and practice law in the United States.

Because STL is the first law school outside of the United States to seek accreditation, it has generated a lot of outside interest and support.

Big-name law firms affiliated with the school include Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld LLP and Paul, Hastings, Janofsky & Walker LLP.

"For us it is important because we depend on Chinese lawyers, most of whom have had to go to the U.S. and get a graduate law degree," said Elliot Cutler, head of Akin Gump's Beijing office. "We've made a multi-year commitment of $25,000 per year for three years. We have also told the school that the conclusion of the student's second year, we will take on a number of their students."

Get the Flash Player to see this player.

Click play to watch a video of the Moot Court

In addition to the big name law firms, renowned legal service provider Thomson West, part of Thomson Reuters, Legal and makers of the legal research tool Westlaw, have also taken an interest in STL. "The legal system in China is only 30 years old," said Chang Wang, global strategist and legal consultant for Thomson West. "With 140,000 lawyers, the legal profession is rapidly growing profession in China. We see a great opportunity for American law."

When STL commenced its first semester, Thomson West provided one-year free of Westlaw, its signature online legal research service used by many American law firms, to all STL students and faculty. They have also provided around 400 free casebooks and study aids for all the students at STL.

The environment encourages students to place themselves in an international mindset. Visiting Professor and Director of Legal Practice Program Howard J. Bromberg notes, "All the instruction is in English and we have the students write constantly. They write all kinds of legal writing with opportunities for rewriting and oral arguments with extensive feedback to perfect their English skills while learning legal skills."

Students are able to hone these skills through a variety of courses and activities, including a moot court competition where they draft legal arguments and present them in front of a judge. The school recruited 40 top Shenzhen lawyers to come to the school and serve as judges for the competition.

Students have their own reasons for attending a novel school like STL, even if it means they won't be practicing law in the future.

Students like Dingmin Liu, who received a degree in English Literature and Language from Zhejiang University, state "Being a lawyer for a whole life seems not very realistic for me. In the US, you have a very strong social atmosphere that advocates the rule of law, while in China we are just strengthening this idea. It would be a very unique experience to be part of the legal contructing process, but to get invovled in the process does not mean one has to be a lawyer...A legal education at STL can provide a unique way of thinking that is applicable in different fields." Immediately upon graduation, Mr. Liu plans to work at a firm for three years and then perhaps start his own business in Ningbo.

Zhang Lining, who graduated with an English degree from Ocean University in Qingdao states, "I was deeply interested and attracted by the school because it gave me chance to use analytical skills. I have an American coach in debating and during training, we analyzed the issues in two different ways. I think in law school, I can be trained as a thinker." While she hasn't ruled out a career in law completely, Zhang has expressed interest in journalism.

The professors at STL admire their students. "They have a hunger that most Americans, myself included, lack. This is their only opportunity -- higher education," said Frank Wu, visiting Professor of Law at Peking STL.

But STL remains an outlier in Chinese legal education. STL's curriculum lacks the staple criminal, civil law, and administrative rule courses that are found in Chinese law schools—the school's aim is not to produce lawyers for the domestic market, but for an international one. "Most of STL's courses are on business law or transnational law," he said. "The emphasis is on training business lawyers who will serve the global market."

Dean Lehman promises that STL will be offering more robust curriculum in the future that spans the profession. There are already immediate plans the following year for Mark Rosenbaum from the ACLU to teach the students about public interest advocacy.

But even if STL only grooms international business lawyers for the time being, the degree offers a quality legal education inside China and possible career advancement for Chinese lawyers working in a foreign law firm based in China. "Currently, foreign law firms are not qualified to practice Chinese law. Chinese lawyers have to relinquish their Chinese qualifications to the Ministry of Justice when they are hired by a foreign firm," said Christopher Stephens, Managing Partner for Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP in Asia.

Unless a Chinese candidate has non-Chinese qualifications when applying at a foreign firm based in China, "law firms can't promote those students because insurance and risk management policies require only to have as associates lawyers that have an active qualification in some country," Stephens said.

Liu further clarifies that "Chinese persons can work in foreign law firms, but not as PRC licensed lawyers, even if they hold the lawyer qualification. The most important things Chinese law graduates [need to have] to find jobs in international firms are English skills and work experience in top Chinese firms. Apparently few law graduates have good work experience in Chinese firms right after their graduation, so English becomes extremely important."

Graph data originally from: Liu, Sida. “Globalization as Boundary-Blurring: International and Local Law Firms in China’s Corporate Law Market.” Law & Society Review, Vol. 42, No. 4 (2008) Pg. 793

For law firms like one that Stephens manages, it's about retaining the best type of Chinese talent possible, perhaps one day even recruiting from STL. "The talent pool across China is wide and deep. It is very competitive, not just among law firms, but investment banks, commercial banks, foreign investors, manufacturing enterprises, and tech companies all chasing this emerging talent." Given STL's emphasis on western law and English skills development, students graduating from STL may be a stronger draw for international firms.

With the education of Western trained Chinese lawyers, what does this mean for the U.S.?

When pressed about whether his school constitutes possibly outsourcing American law, Dean Lehman replied, "I view it less in economics and more in cultural. What we're seeing is the spread and development worldwide of a transnational legal culture where features of different legal cultures and systems are being shared. I think it is good for American society; for American economy if those ideas and principles and systems become part of a shared worldwide vocabulary. The more lawyers everywhere speak American law as well as their own country's law, the better it is for America."

Adds Wang, "I'm very confident STL will get ABA accreditation. The Chinese students specializing in America law help maintain the growth of the international trade and business transaction rather than decrease it. The more Chinese people understand American law, the more Chinese know how to talk to Americans, the more business is created. This means more jobs, transactions, and opportunities will be created for paralegals and junior associates in the United States."

Regardless of whether STL receives accreditation, the school's opening marks another milestone in China's history of legal reform. But for those 54 students working hard to complete the program, accreditation would be a dream come true.

Jaime Mendoza graduated from Loyola Marymount with degrees in Political Science and Asian Pacific Studies.